|

Can #OpenScience make your next grant proposal more competitive, reproducible, and with a solid ground for societal impact? Is there a "section" funder expect you to tick off, and why is that a poor strategy? Where is the EC Evaluator evidence that #OpenScience makes any impact at grant proposal evaluation?

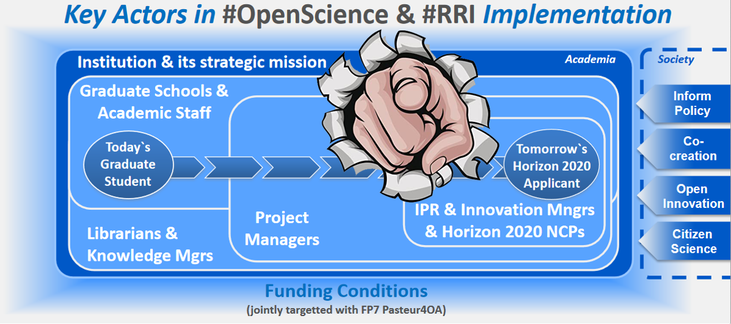

These are some of the questions that fueled the generation of the Winning Horizon2020 with Open Science back in 2015. Since, and thanks to two rounds of funding from H2020 FOSTER and FOSTER+ Projects, the brief for Reseachers, Grants Officers and Research Support staff has been tested in over 100 applications across Horizon 2020 instruments. The societal impact of Open Science has recently been elevated on the global stage, as COVID19 situation yet again reminds us of how much more open research could be. Even if the details are yet to come, EC has made its position clear with respect to Open Science in #HorizonEU for coming 7 years: Open Science is embedded in the WorkProgramme and according to Kostas Glinos (Head of Unit for Open Science at EC) grant applicants will be evaluated on their Open Science performance as part of the "Excellence" criteria. As a result of all this, and inspired by the recent amazing efforts by librarian colleagues at Un. Lille, Lorraine, Strasbourg, it is time to update "Winning Horizon 2020 with Open Science" for the next few years. The goal is to do so with the institutional actors in the Research Ecosystem most likely to need such an aid, and the evidence behind it from the past 5 years of testing. Calling all institutional Open Science Officers, Open Science Ambassadors, Young Researcher Representatives, Grant Officers (with a weakness for Open Science!), NCPs and NOADs that might already be working in the same direction in supporting young researchers and #HorizonEU applicants to MAKE OPEN THE DEFAULT! Contact @OAforClimate on Twitter or via mail.

0 Comments

The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) is currently running a public consultation process to define how research “excellence” should be assessed in future (#REF2021), and many EU Member States are keeping a close eye, as they base their models on the one in the UK.

To stir up the issue, the authors of a recent publication ““Excellence R Us”: university research and the fetishisation of excellence” argue that, “used in its current unqualified form (excellence) is a pernicious and dangerous rhetoric that undermines the very foundations of good scholarship” This is of course not news. Respected members of the academic community all the way up to Nobel winners have repeated the message for some time (cf The Guardian 9 Dec 2013; AAAS CEO Alan Leshner at ESOF2014). The sentiment is again echoed in the London School of Economics Impact Blog opinion piece, and brings painful reality to the debate. The authors argue that “if researchers continue to be assessed using such narrow criteria, scientific research activities will become further dislocated from the needs of the society” and point to examples in developing countries where this is already the case today. Funders recognise the issue, and the European Commission is investing in 2016/2017 research projects to exactly “redefine excellence away from high-profile journal publications and patents alone”, and include other skillset in research performance like transparency, reproducbility, re-use of data, capacity to engage public and citizen science and translate research in the context of societal challenges. Although it may take 3-5 years for the such measure to emerge, and probably even longer for them to be widely accepted, we may need not wait that long to see the detrimental effects. Young researchers applying for competitive grants frequently define the impact of their research by the very narrow criteria criticised above, and the negative impact is very measurable: reproducibility is questioned in fields like psychology and cancer biology, and research grants are less competitive, as “excellence” alone does not secure funds (cf Winning Horizon2020 with Open Science). This poses the question: If current excellence training curricula are based on narrow criteria already being heavily redesigned, is academia doing a dis-service to post-graduates training in a school near you? Should graduate schools wait for the tone to be set, or act early and reshape training focus to match the anticipated broader “excellence” indicators, based on which current graduates will be evaluated by the time they reach mid-career? This may appear as a Catch-22 situation, but for the first schools to move in on the opportunity, the advantage is likely to be significant. Imagine research librarians as equal partners in the research process, helping a researcher in any discipline to map existing knowledge gaps, identify emerging disciplinary crossovers before they even happen, and assist in the formulation and refinement of frontier research questions.

Imagine a librarian armed with the digital tools to automate literature reviews for any discipline, by reducing thousands of articles’ ideas into memes and then applying network analysis to visualise trends in emerging lines of research. What if your research librarian could then dig deeper and use an ami-2word plug-in to map in which sections of articles your key research terms appear? Imagine the results confirmed that your favourite research term almost never appears in the results sections, but cluster only around introductions and perspectives. Imagine a librarian who understands, in pragmatic terms, the benefits of Open Science to the discovery process. Imagine a librarian who also has practical advice on how to make those ideas part of your daily workflow. Would you like that librarian to help you kick-start your academic career? It may sound too good to be true, but in a way it is already happening. Core duties versus ‘stretch’ services The research librarian community is not in consensus as to what exactly are the emerging roles of future librarians in a rapidly evolving digital scholarship environment (see #libraryfutures). Added to the polarised views within that community, a recent survey shows there is also a clear gap in perception and expectations between librarians and faculty staff. While librarians surveyed agreed that “information literacy” and “aiding students one-on-one in conducting research” are primary and essential roles, they viewed “supporting faculty research” as less important than their faculty colleagues. So does this present an opportunity in the digital age? Librarian as co-investigator, not an overhead In the digital age, many of the skills and competencies librarians develop to perform ‘core’ services can actually directly serve the research lifecycle and workflow. Competencies such as mapping the knowledge landscape, digesting volumes of heterogeneous data or presenting in understandable formats are not things every researcher is armed with but which every hypothesis can benefit from. By using their data science and digital skills, research librarians have the opportunity to make an impactful contribution to the workflow of their faculty colleagues. Librarians’ data science skills can help navigate through the deluge of information, and can truly change how they are perceived: from an overhead service to research co-investigators. Despite the opportunities, it would be easy to frustrate the community of librarians by calling for a skills upgrade without contributing in small steps to filling any skills gap. If data science skills are not part of an institution’s strategy, it is difficult to find time and resource to upgrade an individual’s skillset while fulfilling existing contractual obligations. This is where existing structured training philosophies can help with both skills and convincing institutional managers of the strategic benefits of boosting data science capacities. Some examples of data science training include Data Carpentry, Data and Visualization Institute for Librarians, Library Carpentry, Data Science Training 4 Librarians and there are likely many others too. Data science as a driver of Open Science by default As the need for more open and transparent scholarship permeates through funder mandates, research librarians become an indispensable partner in optimally disclosing the diverse outputs of the research process; from advice on choice of appropriate licenses for re-use, to best long-term curation and persistent identifier (PID) assignment in synergy with existing intellectual property rights practices. But to keep in step with the trend, “librarians must provide research data supporting services in the digital age”, and institutions need a structured approach to “enhance research librarians’ data skills, RDM & data services”. The data science skillset of librarians is also considered by some graduate schools (e.g. those engaged with FOSTER Project 2014-2016) to be a deciding factor if Open Science is to form part of the standard skillset taught to postgraduates. To meet Open Science implementation needs, calls for the boosting of institutional data skills extend across disciplines (NSF-NITRD Federal Big Data Research & Development Strategic Plan, May 2016) further downstream to “new skills in data science, data analysis and visualisation” and “text and data mining of content”. Making the future librarian an indispensable research partner to faculty would not only close the gap in how the role is perceived, but also create a self-sustaining conduit for including best practices in collaborative and open scholarship, and implementing Open Science by default. Ultimately, everyone would get more impact. Inspired by Eric Berlow, Paula Masuzzo and my co-authors Jeannette Ekstrom, Mikael Elbaek, Chris Erdmann. Original article was published on LSE Impact Blog (14 Dec 2016) |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed