|

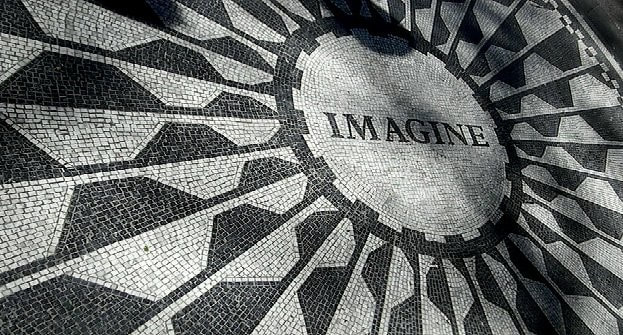

Imagine research librarians as equal partners in the research process, helping a researcher in any discipline to map existing knowledge gaps, identify emerging disciplinary crossovers before they even happen, and assist in the formulation and refinement of frontier research questions.

Imagine a librarian armed with the digital tools to automate literature reviews for any discipline, by reducing thousands of articles’ ideas into memes and then applying network analysis to visualise trends in emerging lines of research. What if your research librarian could then dig deeper and use an ami-2word plug-in to map in which sections of articles your key research terms appear? Imagine the results confirmed that your favourite research term almost never appears in the results sections, but cluster only around introductions and perspectives. Imagine a librarian who understands, in pragmatic terms, the benefits of Open Science to the discovery process. Imagine a librarian who also has practical advice on how to make those ideas part of your daily workflow. Would you like that librarian to help you kick-start your academic career? It may sound too good to be true, but in a way it is already happening. Core duties versus ‘stretch’ services The research librarian community is not in consensus as to what exactly are the emerging roles of future librarians in a rapidly evolving digital scholarship environment (see #libraryfutures). Added to the polarised views within that community, a recent survey shows there is also a clear gap in perception and expectations between librarians and faculty staff. While librarians surveyed agreed that “information literacy” and “aiding students one-on-one in conducting research” are primary and essential roles, they viewed “supporting faculty research” as less important than their faculty colleagues. So does this present an opportunity in the digital age? Librarian as co-investigator, not an overhead In the digital age, many of the skills and competencies librarians develop to perform ‘core’ services can actually directly serve the research lifecycle and workflow. Competencies such as mapping the knowledge landscape, digesting volumes of heterogeneous data or presenting in understandable formats are not things every researcher is armed with but which every hypothesis can benefit from. By using their data science and digital skills, research librarians have the opportunity to make an impactful contribution to the workflow of their faculty colleagues. Librarians’ data science skills can help navigate through the deluge of information, and can truly change how they are perceived: from an overhead service to research co-investigators. Despite the opportunities, it would be easy to frustrate the community of librarians by calling for a skills upgrade without contributing in small steps to filling any skills gap. If data science skills are not part of an institution’s strategy, it is difficult to find time and resource to upgrade an individual’s skillset while fulfilling existing contractual obligations. This is where existing structured training philosophies can help with both skills and convincing institutional managers of the strategic benefits of boosting data science capacities. Some examples of data science training include Data Carpentry, Data and Visualization Institute for Librarians, Library Carpentry, Data Science Training 4 Librarians and there are likely many others too. Data science as a driver of Open Science by default As the need for more open and transparent scholarship permeates through funder mandates, research librarians become an indispensable partner in optimally disclosing the diverse outputs of the research process; from advice on choice of appropriate licenses for re-use, to best long-term curation and persistent identifier (PID) assignment in synergy with existing intellectual property rights practices. But to keep in step with the trend, “librarians must provide research data supporting services in the digital age”, and institutions need a structured approach to “enhance research librarians’ data skills, RDM & data services”. The data science skillset of librarians is also considered by some graduate schools (e.g. those engaged with FOSTER Project 2014-2016) to be a deciding factor if Open Science is to form part of the standard skillset taught to postgraduates. To meet Open Science implementation needs, calls for the boosting of institutional data skills extend across disciplines (NSF-NITRD Federal Big Data Research & Development Strategic Plan, May 2016) further downstream to “new skills in data science, data analysis and visualisation” and “text and data mining of content”. Making the future librarian an indispensable research partner to faculty would not only close the gap in how the role is perceived, but also create a self-sustaining conduit for including best practices in collaborative and open scholarship, and implementing Open Science by default. Ultimately, everyone would get more impact. Inspired by Eric Berlow, Paula Masuzzo and my co-authors Jeannette Ekstrom, Mikael Elbaek, Chris Erdmann. Original article was published on LSE Impact Blog (14 Dec 2016)

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed